Kids were riding around on hoverboards, others were doing homework at the kitchen table and the youngest was getting ready for a bath. Despite the joyful chaos that pervaded the house, there was a tranquility that stemmed from the routine nature of weeknights. As I was welcomed into the house of the family of eight, it was evident that it was a home filled with love and joy. Their dining room was reflective of their Orthodox Jewish faith — decorated with multiple bookshelves of religious texts, objects and pictures of prominent figures. I traveled to this suburban home in upstate New York on a Tuesday night to interview a 10-year-old boy and his parents regarding his long-term struggle with vesicoureteral reflux, non-neurogenic bladder dysfunction, and idiopathic constipation. However, I left with more than I anticipated. I better understood a child’s experience with chronic illness, and how his condition impacted his family’s life and religious observances.

John’s struggles with his health began when he was 7. For a boy who was potty-trained, it was a mystery to his parents when he suddenly began to wet the bed at night. Diagnostic imaging revealed congenital malformations of the ureters and bladder that would eventually require two surgeries between the ages of 7 to 10.

When I asked John how his illness impacted his daily life, he replied, “It does not bother me at all. Everything is fine.” John’s optimistic and joyful character inspired me. Upon further questioning, John revealed that he must self-catheterize four times a day, keep a log of his daily urine and stool volumes, and take daily antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent urinary tract infection. Hearing those facts about his life was surprising, as these medical necessities take up such a substantial part of not only his home life, but time at school as well. John shared that each day at school, there would be a fresh catheter for him in the nurse’s office and after he was done, he would return to class as if nothing had happened. I was glad to hear that aside from occasional complaints about smells from his siblings, there was no bullying or teasing from them or his classmates.

John’s parents are in a delicate situation when it comes to enforcing the health maintenance of their child. If his parents do not remind him about catheters or stool logs often enough or if he gets distracted and forgets, like many children do, he may develop a severe infection and experience further decline in his kidney function. Every time John appears to be a little groggy getting out of bed, his parents question whether he is behaving like a normal child or if it marks the start of an infection that could soon spread throughout his body.

After John and his siblings had been tucked into bed, his parents shared a few more somber thoughts with me. I asked his parents if they could ever see him going away to college and if they believed he would be able to care for himself as an adult. They replied that they had not thought that far into the future yet, but they admitted he recently had to miss out on sleepaway camp — a hallmark of the summer for Orthodox Jewish children that is greatly awaited each year. Unfortunately, John was in Boston this past summer, undergoing surgery on his bladder and ureters. The required downtime after the surgery was multiple weeks and prevented him from joining his siblings and friends at camp. When asked about attending camp in future years, his mother said it does not seem feasible right now and will likely not be in the coming years. They went on to explain that the impact of his illness on their lives and religious observance extended far past summer camp.

Though John’s parents did not delve deeply into the religious dilemma as to why good people experience these types of hardship, they shared how their son’s illness had impacted religious observance. Religion to John as a 10-year-old boy is mostly memorizing and trying to obtain a rudimentary understanding of Bible passages. Yet, as an adult member of his community of faith, John’s father must pray three times a day with other men, which is easy to do with the large Jewish population of upstate New York. It was not so easy during the eight days they had to spend in Boston for John’s surgery. He shared that throughout his family’s journey with the illness, that period was one of the most difficult for him. Fortunately, John’s father is not the type of person who is content with being a victim of circumstance. After that unfortunate event, he realized that maintaining his and his family’s values in spite of the illness would require creativity and dedication to those he loves.

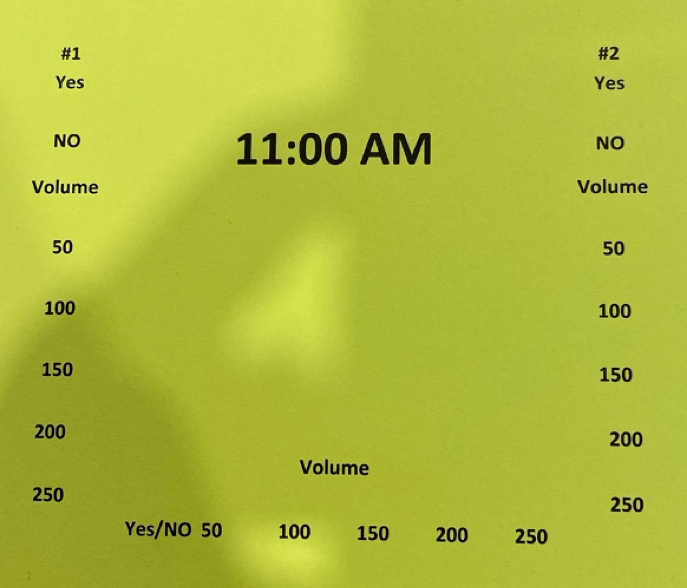

Perhaps the most interesting part of the interview was when John’s father shared that he created a system to record John’s urinary habits via flashcards and paperclips during Shabbat since they are unable to write during that religious observance (see picture above). He also mentioned inspiring stories about the Jewish community being a powerful support system for his family. The community provided him with an apartment in Boston, organized special activities such as swimming and paintball for the children and gave John an iPad to entertain him post-operatively.

John’s mother holds unique insight into navigating parenthood for a child with a chronic illness. She struggled with medical jargon on several occasions. For example, when John was treated for a urinary tract infection, nitrofurantoin was proven to be ineffective due to bacterial resistance, so it had to be replaced with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. This was understandably a confusing concept for her to grasp, and one that she felt was not adequately explained by the medical staff. She has also had long-term struggles with insurance coverage. While John prefers a particular type of pre-lubricated catheter, their insurance company is reluctant to provide coverage for this, requiring a few phone calls before approving a refill. This amounts to less than a week’s supply of catheters at a time, leaving him vulnerable to the very real threat of infection. Though it appears these threats of infection will remain a part of John’s life for the foreseeable future, his family awaits a telehealth visit next month with their doctor to discuss his prognosis. Along with the threat of infection, other constants in John’s life include playing basketball with his friends at school, learning more about his religious faith and experiencing his parents’ deep and genuine love.

This entire experience was a unique opportunity as a medical student. In a way, it transported me back to the past when physicians routinely made house calls and got a sense of the lives of their patients outside of the office. Most importantly, I learned that prioritizing what matters most to your patients is paramount. For John and his family, their priorities were his health and their religious observances. It was a touching affirmation of where I am at in my medical career that after this discussion John’s mother wished I could be present at all of his appointments for clarifications and explanations. This interview has heightened my ability to see patients as a whole. In my future career, when I come across a patient or a patient’s family that possesses a set of cultural values or priorities different from the norm, I will view it as an invitation to make an intimate connection with them so that the delivery of care will be more tailored to their needs. At the core of medicine is compassion, not only for the illness itself, but compassion for what makes each patient so wonderfully unique.

Image credit: Custom artwork by the author for this Mosaic in Medicine piece.