I am a first year family medicine resident in Boone, North Carolina, a CrossFit athlete (since 2012 – and no, I haven’t sacrificed my fitness in pursuit of medicine), a yoga teacher (since 2016) and practitioner (for twenty years). I have been certified in culinary medicine since my second year of medical school due to the influence of my wonderful mentor and coauthor, Dr. Amy Sapola. I entered the field of medicine with dreams of guiding others on self-healing journeys; I live out this dream by disseminating information that enables my patients to recognize their own capacity for healing through changing their nutrition, behaviors and perspectives. Unfortunately, in medical school, I only learned about pharmacologic and surgical interventions for disease, including chronic illnesses that can often be reversed or mitigated much earlier in the process. Examples of this include type two diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, obesity and cardiovascular disease. These ailments dominate Westernized societies worldwide and poor nutrition is consistently identified as one of the strongest risk factors for developing these diseases.

The daily input of nutrition into living bodies is increasingly recognized in population studies as the most important modifiable risk factor for preventable chronic disease. We live in an era in which roughly two thirds of the American diet consists of ultra-processed foods and chronic, worsening metabolic disease has become the expected baseline for patients. In the wake of this crisis, medical schools continue to gloss over topics of nutrition, sleep, movement and stress; however, it is not solely the fault of institutions that these are ignored in medicine. The history of the industrialization of American food has inevitably led us here, underpinned by Western principles of efficiency, calculability, predictability and control. These principles were originally defined by George Ritzer in his book The McDonaldization of Society. Unfortunately, these values have infiltrated and corrupted not only our food supplies and systems, but also our approach to training physicians and models of healthcare delivery. Food production and distribution and medical training and care have been similarly affected due to the prioritization of profit and emphasis on end results that value volume over quality by implementing assembly-line-like protocols.

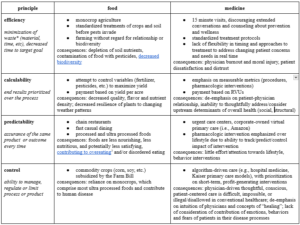

Examples of these parallels can be seen in the below table. Each example in the “medicine” column are from my own experiences as a patient in our sick care system and observations as a medical student on rotations in urban, academic medical centers.

Table 1. Ritzer’s four principles and examples of each in food and medicine.

*Note that minimizing time spent often requires using excess resources (potentially to the point of wastefulness); efficient resource allocation often requires greater time input.

The industrialization of our food and medical care has caused a dramatic shift in values that has ripple effects on the lives and wellness of individuals and communities. The focus on providing food and care that is “cost-efficient” along with policies that favor large corporations has resulted in the merger of both hospitals and farms to become large enough to exist on slim margins driven by large volume, which has resulted in the closure of numerous rural hospitals and small family farms. We all know that there is more to health than doling out prescriptions and that there is so much more to nutrition than obtaining sufficient calories. Fighting for healthier future generations – for people and the planet – necessitates returning to small-scale, community-based models of medical care and agriculture.

Mind-body medicine is an emerging field that is just beginning to elucidate the connectedness of physical wellness to emotions and spirituality. Generalist approaches to healing, particularly those that reject transactional, fee-for-service care in favor of continuity and relationship (such as Direct Primary Care) offer an alternative future for medical care: small scale, with emphasis on unrushed, continuous relationship. Analogously, farming practices developed to sustain, enliven and regenerate the soil that produce food, such as biodynamic and regenerative farming techniques, similarly emphasize the slow and intentional cultivation of healthy soils, leading to higher quality and more nutrient-dense food.

The role of food in medical care and treatment has been given significant attention in recent years with the advent of teaching kitchens in medical schools, culinary medicine training and community programs such as produce prescriptions. The literature strongly supports that diet is the first and most important intervention to prevent, treat and reverse cardiometabolic disease. Studies attempting to quantify the impact of changing relationship with and consumption of foods tend to focus on medically measurable outcomes such as hemoglobin A1c. Ultimately, these studies fail to recognize the importance of the systemic barriers families face when attempting to make behavioral changes because implementing lifestyle changes is heavily influenced by the culture, and the cultures of food and medicine are (currently) defined by the aforementioned values. Without intentionally creating micro-cultures that are radically different from the status quo, randomized controlled trials documenting the impact of single variable changes (e.g., produce prescriptions) will not demonstrate significance. We believe we need studies with both qualitative and quantitative aspects, with emphasis on allocation of time, attention and resources to the cultivation, preparation and conscious, pleasurable consumption of nutritious and delicious foods. Simultaneously, studies need to emphasize the importance of relationship and human connection in medical care to help patients bridge the gap between how they heal and what they eat, and begin to make shifts to their nutrition that align with the complexities of their individual lives.

The antidotes of direct generalist care and biodynamic, regenerative farming models are offered as ideals, but they are occurring here and now in our country by creative, brave individuals and communities with the conviction to create a path to move away from our industrialized systems. Shifting to new models of care and farming require resisting the urge to know and control everything in our environment, and a willingness to shift attention from micro-focusing on single nutrients, disease states or exposures to consider the complexity of the whole system (whether agriculture, medicine or our living bodies). We hope that physicians, farmers and communities can work together to forge a future focused on healing our food and medical systems, which will require that we embrace discomfort with presence, awareness and awe for our world and its inherent wisdom.

When we prioritize profit, product, or both above the relationship we have with living beings (all of our relations: plants, animals and each other), we lose the opportunity to build a spiritual, social and emotional connection that is critical to our sense of humanity. We also lose the slow aspects of our human journey that enable us to mindfully appreciate the moments we are in, to fully acknowledge our needs for nourishment (through nutrition, connection or other ways of healing), and to thoughtfully address those bodily needs, enabling us to return to homeostasis.