Often, a patient or a family member will say something to the effect of “thanks for the update, we will keep praying.” I never know what to say in response. I am a student in the health care field, and I am a Christian; but, in today’s culture, science and religion frequently find themselves estranged. Do I say nothing? Do I offer my own prayers? For what are they praying, specifically? Are they praying for healing? A cure? A miracle? More Faith? Should I pray with them? Should I pray for them? All of these important questions do not get enough consideration. So today I am asking exactly that: what is prayer, and how should we use it? Since the goal of this column is to examine the role of Faith in Medicine, let us think about how prayer should and should not be used in medicine through the following, real-life case.

I was on my very first weekend of my third year of medical school. I was bright eyed and eager to dive into clinical medicine! I still could not find my way around the hospital or navigate the electronic medical record, but I was armed with my stethoscope and ready to learn. While I was rotating through the neurological intensive care unit (ICU) rotation, a patient presented to the emergency department with “altered mental status.” One of the only tasks I was prepared to do was take a history, but the patient was non responsive on arrival. The patient received the full workup of lab tests and imaging that revealed massive subarachnoid hemorrhage. The patient was admitted to the neuro ICU and started on the full spectrum of treatment including intravenous fluids, agents to increase blood pressure, and medications for heart rate and rhythm control. The patient was placed on the mechanical ventilator, and neurosurgery was consulted for the placement of an external ventricular drain. The team of doctors and nurses did all they possibly could, but the patient remained non-responsive.

Later that morning, the attending neuro-intensivist called me to that same patient’s bedside and asked me to demonstrate the neurological exam. I stumbled through a Glascow Coma Scale assessing the patient’s verbal, ocular and motor responses and gave the patient the lowest possible score. I then demonstrated the Full Outline of Unresponsiveness Score exam on the patient, again giving the lowest possible score. Then, at the bedside of the first patient I ever felt honored to call my own, I made my first diagnosis: my patient was brain dead.

My attending decided it was best if he were the one to tell the family, but he invited me to come with him to listen and learn. He gently and firmly told them their loved one had experienced a massive stroke and was diagnosed with irreversible brain death earlier that morning. Tears flowed down every face in the room, including my own, and the attending gave them space to grieve. After some time had passed, the conversation turned to goals of care. The doctor explained the patient could be mechanically ventilated indefinitely, although he was explicit there was no chance brain function would return. The attending continued that the patient could also be removed from the ventilator at which point his death would occur within minutes. The family responded: “Thanks for the update, Doc, we will keep praying.”

At the time, I had so little clinical experience and so little confidence that I said nothing. But in hindsight, I wish I had asked what, specifically, they were praying for. Were they praying for a miracle? Were they praying for thanks that the patient had not suffered a long, slow death? Were they praying angrily at God for taking the life of a loved one? Were they praying for an explanation? If I had only asked, maybe I could have helped guide their prayer and helped their healing.

I do not believe there is a right or wrong way to pray, but I do believe there are wrong things about which to pray. And I believe in miracles, but I do not believe in magic. Let me explain:

I believe prayer is a powerful tool that can be used to connect with God, and I believe prayer is a powerful form of introspection and self-reflection that should be a part of every person’s daily life. And whether you call it prayer or not, I think most people already pray every single day! Prayer comes in many different forms. For some, prayer is an explicit time to speak out loud to God. Some people pray in silence with their eyes closed. For others, prayer looks like meditation or yoga. Some people pray in poetry and art, and others pray through music and dance. Some pray when they listen to music in the car on the way to work. Others pray when they walk their dog. I think most people find time each day that they feel connected, unified, in some way, to something larger than themselves. Everybody prays, and those prayers go by many different names.

While there is not a right or wrong way to pray, there are wrong things about which to pray. Prayer is not some magical incantation spoken to change the physical structure of the universe or defy the known laws of physics. I do not pray after my exams “Dear God, please give me a good grade on that test.” I have already submitted the exam. Prayer cannot change the answers that I submitted. Likewise, prayer does not have the ability to physically evacuate blood from the ventricles of my patient and reperfuse his brainstem. Prayer is not going to bring back my patient from death. Rather, prayer is a means of communication and self-reflection. Prayer is communicative in that it allows a person to communicate directly with God, and it is self-reflective in that it allows a person to examine oneself and allows a person to examine his or her relationships with others. After my exams, I pray to communicate with God my frustration that the test was difficult, that I was underprepared, that I am tired of not feeling smart enough, and that I fear I will not be a good physician. If I can muster the positive energy, I pray a prayer of thanksgiving that I am privileged enough to be in medical school, and I pray a prayer of thanksgiving that I have a loving wife and family who support me no matter what.

Likewise, I prayed for my patient and his family that through this tragedy the family could grow closer together. I prayed a prayer of sadness for the loss of my patient. I prayed a prayer of gratitude for the life my patient lived and the impact he had on those he knew. I prayed for the family of my patient that they might be comforted by God’s presence as they grieved. I prayed that through their grief they might find peace. And I prayed a prayer of thanksgiving for the dozens of doctors, nurses and other staff who cared for my patient. I prayed that scientists and researchers would continue to study and learn and develop new treatments and therapies that might improve outcomes for patients such as mine.

Today I pray for each of my patients that they might be treated effectively and kindly by their doctors and nurses. I pray they feel God’s presence in that process. I pray for the families of these patients that they feel peace as they struggle with difficult diagnoses and treatment plans. I pray for doctors and nurses to provide the highest quality care possible, and I pray they do it with grace. And finally, I pray for each of you reading this. I pray that your studies are going well. I pray you are finding joy in your work. I pray you are finding time away from your work. And I pray that you would consider the role of prayer in your own lives, in whatever form comes most naturally to you.

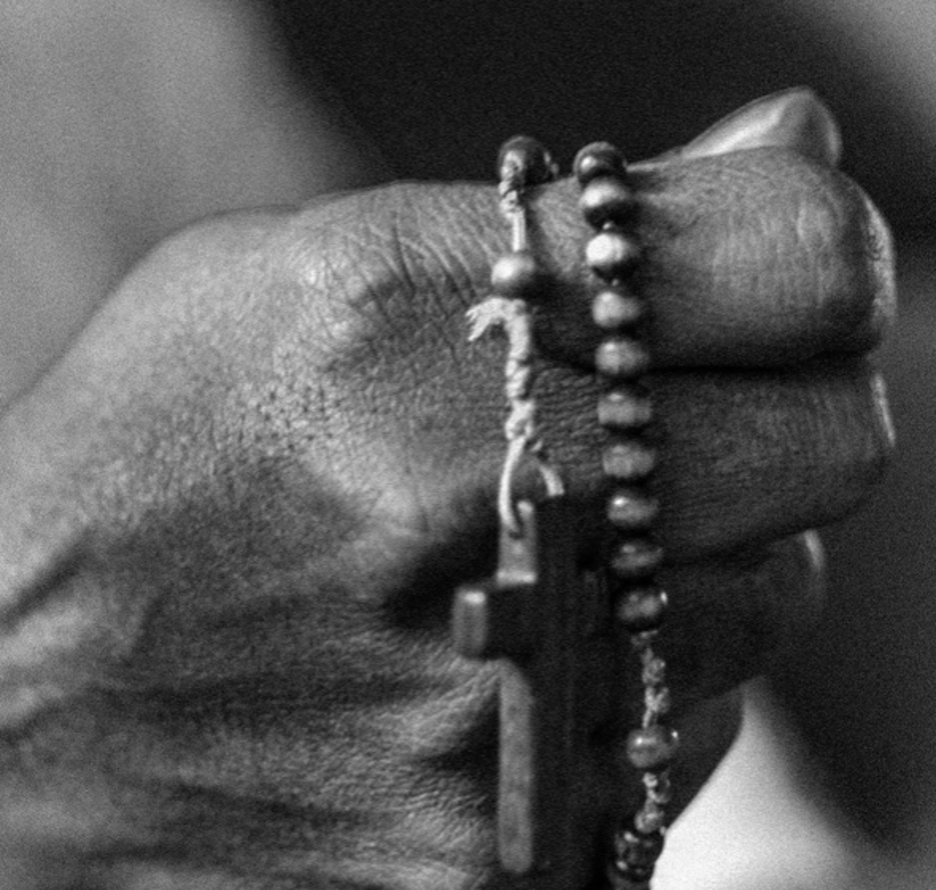

Image credit: Prayer by EssamSaad is licensed under CC BY 2.0